|

|

|

The core primary care functions are proven to have a positive impact on the quality of service delivery and the experience of patients.

Thus, every country should make it a priority to better measure and achieve the core primary care functions.

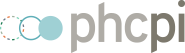

Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” is distinguished by the core functions it provides:

- First contact accessibility refers to the capacity of a primary care system to serve as the first point of contact, or a patient’s entry point to the health system, for most of a person’s health needs.

- Comprehensiveness Comprehensiveness refers to the provision of holistic and appropriate care across a broad spectrum of health problems, age ranges, and treatment modalities. Comprehensive care should address a wide range of preventive, promotive, chronic, behavioural, and rehabilitative services and include an assessment of a patient’s risks, needs, and preferences at the primary care level. refers to the provision of holistic and appropriate care across a broad spectrum of health needs, ages, and solutions. Comprehensive primary health care is able to address a majority of promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative, chronic and palliative service needs.

- Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. of care refers to the system's ability to oversee and manage patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. of care happens across levels of care and over time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams and consistent tracking and communication of progress.

- Continuity “Continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. is the degree to which a patient experiences a series of discrete healthcare events as coherent and consistent with their medical needs and personal context. This requires fostering trusted relationships between health care providers and patients over time (relational continuity), ensuring information is communicated from one event to the next (informational continuity), and ensuring the process is managed in a timely, complementary, and effective way across providers (management continuity).

- People-centeredness means organizing the health system around the comprehensive needs of people rather than individual diseases. This involves engaging with people, families, and communities as equal partners in promoting and maintaining their health - including through communication, trust, and respect for preferences, as well as ongoing education and support so that they can participate in health care decisions.

High-quality primary health care systems consistently deliver services that are trusted and valued by the people they serve and improve health outcomes for all. 123456 Vulnerable groups often face the most barriers to accessing high-quality PHC. Therefore, health systems should take into account people’s unique social determinants of health (SDOH) when planning, designing, and implementing PHC programmes. 4

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

The core primary care functions are proven to have a positive impact on the quality of service delivery and the experience of patients. Thus, every country should make it a priority to better measure and achieve the core primary care functions. 789

Before taking action, countries should first determine where to target measurement and improvement efforts. Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second generation Vital Signs Profile measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. The core primary care functions are measured in the quality domain of the VSP (performance pillar)

If a country does not have a VSP, it can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

Countries that do not have a VSP can use the following indications to help start to identify where to focus improvement efforts:

Indications for first-contact accessibility:

- Acceptability barriers: high utilization rates of inpatient, specialist and/or emergency care often reflect a lack of trust or confidence for PHC as the preferred first point of care

- Access barriers: if a significant portion and/or specific segments of the population do not have a usual source of care this may reflect the presence of access barriers related to timeliness, financial access, or geographic access from the patient perspective

- Poor quality or untimely services: a lack of utilization could reflect broader system inefficiencies, such as inadequate facilities and shortages of skilled workforce that ultimately lead to low levels of public trust and confidence in the system, pushing patients to other levels of care

- Fragmented commitment to primary care: when national policies, plans, and activities are fragmented or not in place at all, this often limits their ability to reinforce primary care as the first point of care (such as empanelment) and reduce access barriers for patients

Indications for comprehensiveness:

- Fragmented programs: when health services are delivered through vertical programs with misaligned, disease-focused targets and incentives, then this can lead to the fragmentation of programs and services throughout the health system. Specifically, vertical programs can lead to 1) the creation of parallel systems for funding and management; 2) the distortion of national priorities and 3) a lack of contribution to the overall strengthening of the health care system. 1011 In addition, a vertical approach discourages the delivery of comprehensive care, since vertical programs focus on managing the health of populations with a single disease condition, rather than holistic needs of the population. 1213

- Lack of intersectoral action and accountability: if there is no policy or accountability structure, health systems lose their ability to promote multisectoral collaboration or action for health and wellbeing across various sectors

- Insufficient inputs: when there is a lack of necessary inputs (infrastructure, workforce, supplies and technology systems), PHC facilities are not equipped with the necessary equipment, methods and medications to prevent, diagnose, and treat a wide range of problems

- Lack of provider motivation and competence: when providers or organizations receive little to no incentives, trainings, or operational support, then their ability to provide holistic, comprehensive and high-quality care is diminished

- Poor governance levers: a lack of robust policies and infrastructure will inhibit the health system’s ability to implement models of care that promote integrated, people-centred PHC at the frontline

- Poor health outcomes: if care is not comprehensive, the population is likely to experience significant morbidity and mortality from preventative causes

Indications for continuity:

- Weak information systems: when systems for gathering and sharing information and data across various levels of care are not functioning properly (i.e. not interoperable or interconnected, poor quality etc.), then they cannot be used to promote a continuous care experience

- Barriers to timely access: a lack of timely access to care often results in long wait times to see providers and large amounts of overcrowding at PHC and non-PHC facilities which ultimately hinder their access to continuous care

- Poor patient-provider relationships: if primary care teams are not well-managed or care items are not appropriately communicated to patients and systems then this interferes with timely and complementary service delivery as well as indicates the need to improve patient-provider relationships

- Inconsistent care: if care management plans are not adaptive to a patient’s complex needs and there is a lack of consistent care teams, then a patient’s care experience can be highly disrupted

Indications for coordination:

- Poor patient experience: if patients do not have continuous relationships with their care providers, this can contribute to a low-quality patient experience as their providers won’t know their care history and have the ability to facilitate connections within the community and to certain resources

- System fragmentation: if the system is fragmented this often leads to systematic misalignment of incentives and intersectoral organizations that ultimately lead to inefficiencies that disrupt care and can harm patients

- Lack of support for providers: when providers or organizations receive little to no incentives, trainings, or other kinds of operational support then their ability to support coordinated care is often hindered

- Low or mismatched care-seeking behaviour: poor coordination and a lack of an integrated health system results in over-utilization of higher levels of care for needs that can be addressed at the primary care level

- Lack of governance and accountability: when there is a lack of accountability at the governing level, there is often no formal policy structure to promote collaboration or disincentive market structures that compensate providers for multiple point-of-care interactions

- Informational inefficiency: when there is a lack of robust information systems, then the ability to coordinate communication and track and support patients becomes very difficult

Indications for people-centredness:

- Poor quality and distrust: if people-centred care is not a priority then patients often feel that their care is of poor quality and do not have established longitudinal relationships with care providers who know their care history

- Lack of support for providers: poor people-centeredness in the health system often means providers or organizations receive little to no incentives, trainings, or operation support for providing holistic quality care

- Low patient engagement: when patients are not engaged in the health system, then a significant portion of the population does not have the educational support to make informed decisions about their care

- Lack of governance and accountability: if there is no accountability at the government level there tends to be no formal system for a participatory approach to policy formulation, decision-making, and performance evaluation that is seen at all levels of the health system

- Low or mismatched care-seeking behaviour: when care-seeking behaviour is less than optimal then patients are typically under-utilizing care altogether or over-utilizing higher levels of care for needs that can be addressed at the primary care level

- Poor health outcomes: poor people-centred care often means the population is experiencing significant morbidity and mortality from preventative causes

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that improve primary care functions in their health system may achieve the following outcomes and impact: 59141516

- Increased patient and workforce satisfaction: Services that deliver on the core primary care functions can improve the experience of care for both patients and providers.

- Service quality and health systems strengthening: They can also improve the quality of care, enhance patient health outcomes, and contribute to improved health system performance. For example, enhanced continuity and coordination of care can help to improve the flow of information and resources across care sites, which helps to reduce fragmentation and other inefficiencies in a health system.

- Equity: Lastly, comprehensive, people-centred models of care help to ensure that equity is a priority in both public and private health systems and that patients’ holistic needs are met. Furthermore, first contact access, continuity, and coordination of care mechanisms help to ensure that no one is left behind.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this section for a curated list of actions that countries can take to achieve the primary care functions in their context, which embark on:

- Explaining why the action is important for population health management

- Describing activities/interventions countries can implement to improve

- Describing the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximize the success/impact of actions

- Curating relevant case studies, tools, &/or resources that showcase what other countries around the world are doing to improve as well as select tools and resources.

Key actions:

-

High-quality PHC can meet 90% of a population's health needs and should be patients’ first and regular point of contact. First contact access helps to bring care as close as possible to communities, which is essential to UHC. It is related to improved technical and experiential outcomes, as well as reduced utilization of unnecessary emergency and inpatient services. 281718

To be an effective first point of contact, primary care centres and/or health workers must consistently deliver services that users trust, value, and can easily access and afford. 789 Key activities countries can take to ensure this are outlined below.

Key activities

National and sub-national levels

- Reaffirm leaders’ commitments to UHC and promote PHC-oriented models of care. To aid in this step:

- Recognize the need to tackle inequities in health care access and quality via political declarations on UHC, with PHC as the foundation for coverage. 19

- Formalize these commitments via statutes, regulations, and policy and financing mechanisms. 2021222324 See the action “develop quality management infrastructure” for additional guidance.

- Organize health system structures in a way that directs patients to primary care as the first point of contact and supports the other primary care functions. For example, develop a comprehensive and include a wide range of stakeholders in national and local planning processes. 18

- Invest in quality. Health systems that improve access to and quality of PHC tend to see increased rates of primary health care utilization. 50 Quality is a cross-cutting concept. For additional guidance on how to improve it at different levels of the health system, navigate to the take action section of the service quality module and select the dropdown “strengthen systems for improving the quality of care”.

- Invest in reliable, high-quality inputs. This helps to ensure that patients can access needed services at the point of care and that health workers are well-equipped to deliver these services. 25 To aid in this step:

- Strengthen physical infrastructure: Improve the design, density, and distribution of primary care centres. For example, co-design facilities and services with patients to ensure they meet their needs, values, and preferences. 2627 In addition, offer community-based services for conditions that can be managed outside the facility. Mobile clinics can also help to bring primary care closer due to communities. However, by nature of being mobile, these clinics will not contribute to the formation of continuous relationships between patients and providers. 8

- Build a skilled and motivated workforce: Addressing workforce shortages and skills gaps can help to increase patient trust in PHC as the first point of contact. In addition, organizing the health workforce into care teams can make PHC offerings more comprehensive and strengthen coordination of care. 2829

- Realign referral systems. To promote primary care as the first point of contact, referral systems should align with existing empanelment and gatekeeping structures and promote bidirectional referrals. 30

All levels

- Empower individuals, families, and communities to manage and make informed decisions about their health and well-being, including awareness about the importance of a continuous relationship with their primary care team. 4862 In addition, leaders should actively solicit and integrate their input into the design and delivery of health services. Doing helps to ensure that services meet their needs and can increase patient satisfaction and trust in the health system. 47484950 For additional guidance, see the sub-action “engage and empower patients, families, and communities” in the service quality module and the deep dive on “services for health literacy and self-care” in the population health management module.

- Partner with the private sector. in many LMICs, private clinics may be the first point of contact. 831 In countries where the demand for public primary care services is low relative to the demand for private services, there is a potential to improve first-contact access via partnerships with the private sector. 32

- Introduce interventions that bring services to the patient. as discussed above, community-based services and mobile clinics can enhance access to PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. . Telehealth services are also an efficient way to bring high-quality PHC to the patient. 33

- Ease financial and geographic access barriers. there are many interventions that countries can implement to help patients overcome barriers to accessing services. For example, they may assign transportation vouchers or user fee waivers. For additional guidance, see the access module.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Access

- Population health management

- Health workforce

- Funding & allocation of resources

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2018: WHO Technical Series Document on the Private Sector, Universal Health Coverage and Primary Care

- WHO, 2016: Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030 report

- International Center for Social Franchising, 2015: Scaling up Primary Care to Improve Health in Low and Middle-Income Countries

- WHO,2013: WHO Framework for Action Toward Coordinated/Integrated Health Services Delivery

- Reaffirm leaders’ commitments to UHC and promote PHC-oriented models of care. To aid in this step:

-

Continuity “Continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. and coordination of care are interrelated concepts that help to reduce fragmentation and thus improve the quality of care. 16343536 Because there is some overlap between elements of continuity and care coordination, we organize the key activities below in a way that amplifies their effect at various stages of the care pathway: 16

Create an enabling environment for care coordination by increasing relational continuity and implementing protocols, pathways, financial incentives, and information and communication technology (ICT) that support seamless interactions within and across care sites.

Within this enabling environment, use clinical coordination mechanisms to enhance management and informational continuity of care over time.

Sub-action 1. Create an enabling environment for continuity & care coordination

Key activities

All levels

- Organize services in a way that promotes continuity and coordination of care. For example, establish systems for referral and counter-referrals, implement team-based care models, and clearly define pathways for care within and across care settings and sectors. In addition, establish integrated, people-centred models of care. 8

- Promote . Redefining facility roles within a vertically integrated network will require collaboration and cooperation among health facilities at different levels of the health care system. This process will define the range of services facilities will provide and it will determine how facilities will support each other across levels of care through supervision mechanisms, technical assistance, and partnerships (such as accountable care organizations). To aid in this transition, clearly defined contracts, payment, and incentive structures should be in place. 30

- Invest in reliable, high-quality inputs. This helps to ensure that patients can access needed services at the point of care and that health workers are well-equipped to deliver these services. 25 To aid in this step:

- Improve the design, density, and distribution of primary care centres. For example, co-design facilities and services with patients to ensure they meet their needs, values, and preferences. 2627 In addition, offer community-based services for conditions that can be managed outside the facility. To promote continuity and coordination of care, ensure that community- and facility-based providers are linked by information and communication technology (i.e. telephone, SMS, etc.) 8 and develop formalized facility networks based on

- Ensure that health workers are skilled, motivated, and available to deliver quality health care services. To aid in this step, define the health worker competencies in relation to the PHC service package and organize them into efficient care teams. Provide them with the requisite incentives, education, and training needed to make this transition to team-based care and clearly define each team member’s role. 8192829

- Ensure access to medicines and supplies. Make sure that facility- and community-based providers have the high-quality medicines and supplies at the right time. Furthermore, use However, even if patients can access and afford these products they may not necessarily take them as intended. For example, patients may not take medicines as prescribed because they forget or they are bothered by the side effects. Strong relational continuity (below) can help to ensure that patients understand their conditions and medicines, give them opportunities to tailor their plan to their needs and preferences, and thus, enhance adherence to treatment plans. 83738

- Strengthen information and communication technology for health. Develop/introduce information systems that connect a wide range of data sources across different settings of care and reliably communicate this information at the right time and to the right people. This includes communicating information to higher levels of care and back to the frontline. The coordinated exchange of information should enable all health workers involved in a person’s care to access, exchange, and use information with the goal of optimising patient well-being. 16343940

- Use quality improvement methods and tools to assess and improve continuity and coordination of care. For example, use shared decision-making and self-management tools to support patients and families in making informed decisions about their health. Use evidence-based clinical guidelines to hold providers accountable for the delivery of high-quality services within and between sectors. See the take action section of the service quality module for additional guidance.

At the point of care and in communities

- Increase relational continuity:

- Strive to build and retain a consistent core staff that share language and values with their target community. 3441 To aid in this step leaders should ensure that health workers have the core competencies and resources needed for people-centred care. For example, health workers should be trained in the core primary care functions and have access to supportive supervision.

- Nurture relationships with patients and adapt care to meet their unique needs, values, and preferences over time. 16343536 To aid in this step, care teams should consider developing a collaborative care plan with patients. 344243 They should also practice active listening, facilitate patient engagement, and show accountability to patient needs. 344243

- Deliver care in a predictable and familiar environment that patients can easily access. 16343536

- Provide to patients, which means that a consistent team of providers manage a patient’s care throughout their life course. 16343536 To aid in this step, facilities should consider recruiting health workers directly from the local community, which can help to improve health workforce retention and . 44454647

- Prepare patients for discharge at the moment of admission, including what their care needs are once they go home and who will care for them. Share and coordinate this discharge plan with the patient's primary care provider in a timely manner. 164849

- Establish links and referral strategies for all professionals involved in a patient’s care. For example, care teams should use clinical care pathways and referral protocols to manage a patient’s care. 16

- Link patients with a care navigator or community connector to ensure that patients have the support they need to manage their condition and navigate the health system. 16

- Capacitate patients to actively participate in and manage their care. For example, health system and/or facility leaders should promote services for health literacy and self-care, such as peer support groups and self-management education. 16

Sub-action 2. Enhance and reinforce coordination & continuity of care over time

Key activities

At the point of care and in communities

- Implement sequential clinical coordination mechanisms:

- Promote a shared, collaborative single point of entry to care with primary care as the first point of contact

- Promote collaborative case management within and across care sites and sectors. 1650 To aid in this step:

- Implement and use ICT systems that teams to securely share patient information across care boundaries. Examples include two-way referral networks, electronic health records, and secure instant messaging apps, among others. 50

- Coordinate care plans and discharge planning across sectors and care sites. For example, improve cross-sectoral collaboration in service delivery via joint projects or programs with local community agencies/CSOs, private sector organizations, and or other public sectors.

- Collocate services and multidisciplinary professionals in the same facility.

- Use evidence-based clinical pathways, guidelines, and protocols to reduce variations in care across care sites and sectors. In addition, use clinical care pathways to ensure that care teams follow clinical care pathways and diagnostic protocols across sites. 5051

- Reinforce patient-provider communication. Because patients are a part of the care team, they should be informed of what and why their care is changing. To aid in this step, providers should practice active listening and co-develop care plans during clinical encounters. In between visits, care teams should share time-sensitive information with patients (i.e. test results, need for a follow-up visit, etc.) via secure communication portals. 5253

- Keep care timely. It is important for primary care systems and facilities to balance the often conflicting metrics of timely access and physician continuity. For additional guidance on how to make care more timely, see the “key actions” section of the service quality module.

- Ensure no patients get left behind via a community, based proactive approach that involves case finding, assessment, care planning, and coordination with sectors and levels of care.

- Implement parallel clinical coordination mechanisms:

- Build strong multidisciplinary care teams and reinforce a culture of collaboration, communication, and shared decision-making.

- Introduce a ‘care coordinator’ role within the facility or organisation

- Implement quality interventions that enhance patient, family, and community engagement (i.e. individualized and tailored care plans, self-management support, formal or joint-assessment tools)

- Implement quality interventions that increase the accountability of care teams and organizations to patient needs (i.e. primary care assessment tools, joint goal-setting exercises, etc.)

- Institutionalise continuing education and supportive supervision processes to ensure that care teams have the capacities they need to deliver coordinated care

Relevant tools & resources

- Joint Learning Network, 2018: JLN Vertical Integration Virtual Learning Exchange

- WHO, 2018: Continuity “Continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. and coordination of care: a practice brief to support the implementation of the WHO Framework on integrated people-centred health services

- WHO, 2018: Report on multi-sectoral and intersectoral action for health and well-being for all

- AHRQ, 2016: Care Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. Measures Atlas

- AHRQ, 2016: Care Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. Quality Measure for Primary Care

- World Bank, 2014: Global Scaling Up Investment Plan

- Measure Evaluation, 2013: Referral Systems Assessment and Monitoring Toolkit

- WHO, 2013: WHO Framework for Action Toward Coordinated/Integrated Health Services Delivery

- AHRQ, 2011: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality page on care coordination

- WHO, 2006: Medical Records Manual: a Guide for Developing Countries

- Safety Safety refers to the practice of following procedures and guidelines in the delivery of PHC services in order to avoid harm to the people for whom care is intended. Medical Net Home Initiative: Continuous & team-based healing relationships

- Safety Safety refers to the practice of following procedures and guidelines in the delivery of PHC services in order to avoid harm to the people for whom care is intended. Medical Net Home Initiative: Care coordination

-

Comprehensive, people-centred models of care can generate many benefits for a health system, including improved access to care, improved health and clinical outcomes, better health literacy and self-care, increased patient and provider satisfaction with their experience of care, improved efficiency of services, and reduced overall costs. 13545556

All of the previous actions and sub-actions can help to reinforce comprehensive, people-centred models of care. Additional activities to consider include:

Key activities

National and sub-national levels

- Move from a vertical to an integrated approach. An “integrated” approach focuses on building one overarching plan, budget, and accountability framework for the health sector. Under this model, vertical programmes are encouraged to align their requirements with the health sector strategic plan. In recent years, many country plans have put PHC as at the centre of these plans. This has allowed countries to better deploy and coordinate infrastructure, resources, and processes across vertical programs for PHC. For example, many countries have included basic HIV, TB, and newborn and child in the essential package of health services, thus supporting a shift to more comprehensive PHC. 101157 For additional guidance, see the ‘promote people-centred, delivery’ action in the service quality module.

- Develop a more comprehensive essential package of health services. Building on the integrated approach above, countries must strive to go beyond a minimum package of health services to cover a comprehensive and integrated range of services. Comprehensive services should cover health protection, prevention, management, and palliation across key life course needs and disease programs including emergency situations, reproductive health, growth, development, disability, ageing, communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases, mental health, and violence and injury. 14 The specific services prioritised within each need will differ between settings. Read more in the organisation of services module.

- Leverage a holistic, multisectoral approach. A multisectoral approach in health (i.e. Health in All Policies) promotes comprehensiveness by engaging other services and sectors both directly and indirectly involved in the health of people and communities. 13585960

- Social participation. Encouraging broader social participation in the policy process (such as citizen groups and media platforms) helps to strengthen accountability across sectors and forge collaborative partnerships for more comprehensive initiatives. 60

- A rights-based approach to reform. People-centred reforms incorporate a rights-based approach to health systems strengthening, placing health as a human right at the core of the national health strategy. 55

- Strive for quality improvement and safety, including via continuous quality improvement, quality assurance, and a culture of safety. 55 For additional guidance, see the following ‘strengthen systems for improving the quality of care’ action in the service quality module.

At the point of care and in communities

- Comprehensive, people-centred services put patient needs and values front and centre. While expectations and approaches to people-centred care vary between countries, it generally means 23

- Services meet communities’ unique needs and preferences. To meet patients’ needs, countries must successfully engage patients, families, and communities in all aspects of design, planning, governance, and delivery of health care services. (23, 108, 109) See the sub-action for engaging patients, families, and communities for additional guidance.

- Services are delivered with compassion and respect. Compassion Compassion is the emotional response to another person’s suffering and the authentic desire to take action to relieve their pain or suffering in some way. has important links to the quality of care. For example, studies have shown that compassion and the touch of a trusted other can help to alleviate another person's experience of pain and to improve stress-related disease. 2390

- Services promote patient activation, health literacy, and self-care. Engaging and empowering people to participate in their own care is essential to improving health outcomes,increasing patient satisfaction, reducing costs, and improving the clinician experience. Shared decision making is one of the most important approaches to achieve this engagement: patients and providers work together to make decisions and select treatments and care plans.(23,110)

Related elements

- Policies & leadership

- Population health management

- Health workforce

- Management of services

- Funding & allocation of resources

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2021: Fostering resilience through integrated health system strengthening: technical meeting report

- CGD, 2020: Getting to Convergence: How “Vertical” Health Programs Add Up to A Health System

- R4D, 2019: Should vertical programs be integrated into primary health care?

- WHO, 2018: WHO Technical Series on Primary Care

- WHO, 2018: WHO report on multi-sectoral and intersectoral action for health and well-being for all

- WHO, 2016: Integrated Care Models: An Overview

- WHO, 2016: WHO Framework on Integrated, People-Centered Services

- WHO, 2016: WHO Health in All Policies Framework ( HiAP “An approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the implications for health and health systems of decisions, seeks collaborations, and avoids harmful health impacts in order to improve population health and health equity. A Health in All Policies approach is founded on health-related rights and obligations. It emphasizes the effect of public policies on health determinants and aims to improve the accountability of policy-makers for the effects on health of all levels of policymaking.” )

- WHO, 2016: Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030 report

- WHO, 2015: Health in all Policies Training Manual

- WHO, 2013: WHO Package on Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care in Low-Resource Settings

- WHO, 2013: WHO Framework for Action Toward Coordinated/Integrated Health Services Delivery

- WHO, 2002: WHO Integrated Management of Adolescent and Adult Illness modules

- PAI: Integrating Vertical Programs into Primary Health Care

- Family Care Network, 2009: Minnesota Complexity Assessment Method

- Patient Reported Outcome Tools:

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, service availability & readiness. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact service quality, some of the major drivers are listed below. To aid in the prioritization process, we group the ‘related elements’ into:

Upstream elements

We define “upstream elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make the biggest impact, whether positive or negative, on the primary care functions.

- Policy & leadership

-

Policy and leadership impact primary care functions in a multitude of ways:

- Comprehensiveness: PHC policies that prioritize integrated service delivery and an expanded service package at the PHC level promote comprehensiveness in the breadth of services provided

- Coordination: Central policy directives can promote coordination through the definition of vertically and horizontally integrated care networks, engagement of the private sector, and establishing referral networks.

- First-contact accessibility: Supportive PHC policies establish system orientation, financing, inputs, and service delivery mechanisms, such as gatekeeping and empanelment structures, to promote PHC as the first point of contact into the health system.

- People-centeredness: National policies can support people-centeredness by ensuring a rights-based approach to health and establishing a model of care centred around the holistic needs of individuals and communities.

- Information & technology

-

Information & technology impacts primary care functions in a multitude of ways:

- Coordination: coordination relies on the ability of information systems to connect, in a seamless manner, a wide range of data sources across different settings of care and sectors in order to reliably communicate this information at the right time and to the right people.

- Continuity: continuity of care relies on information systems with broad capacities to track and manage the health of a patient, including interoperable systems across facilities and comprehensive patient care records.

- First-contact accessibility: information and technology infrastructure, such as mHealth and telehealth, can facilitate access to PHC where clinics are inaccessible but sufficient technological infrastructure is in place.

- Comprehensiveness: data collected through surveillance and other information streams are important for supplementing decisions around which services to provide within a comprehensive service delivery package.

- Population health management

-

Population health management impacts primary care functions in a multitude of ways:

- Comprehensiveness: empanelment to multidisciplinary care teams supports the provision of proactive and comprehensive PHC

- People-centeredness: local priority setting ensures health services and local action plans are tailored to meet the needs and interests of the communities they are designed to serve. Community engagement mechanisms ensure patient involvement in decision-making and planning processes and create channels for holding governments and providers accountable. Effective empanelment requires the assumption of responsibility for the health and well-being of a target population, including providing proactive primary health services based on each individual's health status, which is a necessary step in moving towards people-centred integrated care.

- Coordination: empanelment establishes the denominator of individuals for whom a specific care team is responsible and can be used to support the development and implementation of coordination mechanisms such as referral pathways.

- Continuity: empanelment fosters longitudinal relationships between individuals and their care teams that can foster continuity over time.

- First-contact accessibility: community engagement can help build awareness of and confidence in PHC services to encourage first-contact access. Empanelment establishes a point of care for individuals and simultaneously holds providers and care teams accountable for actively managing the care of their panels, helping to support first contact access. Proactive service delivery mechanisms can help to facilitate primary care as the first point of contact by bringing services to the community.

- Organisation of services

-

Organization of services impacts primary care functions in a multitude of ways:

- Comprehensiveness: selection and delivery of PHC services by differing facility types, including defining essential service packages and care standards for these conditions, is critical in ensuring that a comprehensive set of high-quality services are available to a population.

- Coordination: interoperable referral systems from lower to higher level facilities (and vice versa) are essential to promoting coordinated care across facilities and levels of service. It's especially critical for ensuring appropriate follow-up treatment at the PHC level.

- Continuity: interoperable systems of referral complement can aid in a patient experiencing transfers of care between PHC levels and facilities as coherent and connected.

- People-centeredness: it is important that the selection, organization, and provision of PHC services is people-centred and reflective of community needs.

- Management of services

-

Management of services impacts primary care functions in a multitude of ways:

- First-contact accessibility: in decentralized contexts, funds will often play the same role as spending on PHC. Therefore, appropriate management of these funds at the facility level is critical to maintaining facility functioning and maintaining PHC as the first point of contact.

- Comprehensiveness: multidisciplinary care teams can support the expansion of the service package delivered at the PHC level and therefore improve comprehensiveness.

- People-centeredness: facility leadership's commitment to people-centeredness supports the implementation of people-centred models of care. Quality interventions for engaging patients, families, and communities in their care support people-centeredness.

- Coordination: quality management infrastructure at the facility level ensures quality interventions such as standardized care plans, diagnostic protocols, accreditation systems, etc. are in place across providers and facilities, promoting a continuous and coordinated care experience.

- Continuity: quality management infrastructures ensure quality interventions such as standardized care plans, diagnostic protocols, accreditation systems, etc. are in place across providers and facilities, promoting a continuous and coordinated care experience.

- Service availability & readiness

-

Service availability and readiness can impact primary care functions in a multitude of ways:

- First-contact accessibility: PHC workforce must be consistently available at the facility (and/or in communities) to enable first-contact access and build confidence in PHC from the local population. The workforce must have the competencies to provide a comprehensive set of services in order for PHC to be the first point of contact for the majority of population health needs. Patient-provider respect and trust build confidence in the PHC system and encourage patients to make PHC their first and main source of care.

- Comprehensiveness: to achieve comprehensiveness, the PHC workforce must be trained and competent in a broad range of service types.

- People-centeredness: patient-provider respect and trust help to ensure PHC services are trusted and valued by users through supporting shared decision-making.

- Continuity: respect and trust between providers and patients can improve communication and provider motivation and contribute to the formation of continuous relationships over time.

- Purchasing & payment systems

-

Purchasing and payment systems serve to define the comprehensiveness and availability of care that is delivered. Payment systems in particular can incentivize the quality of care that is delivered. Purchasing and payment systems also work to incentivize and/or create platforms for care coordination, helping to improve the quality of primary care functions.

- Access

-

Even if services are present and high-quality at the point of care, if users experience barriers to accessing and using it, primary care can not effectively serve as the first point of contact. In order for services to be considered accessible, patients can’t face any actual or perceived barriers to receiving services in terms of geographic proximity, cost, convenient hours of operation and waiting times. The accessibility of services hinges on primary care facility infrastructure, including the physical availability, number, mix, and distribution of facilities, both private and public, throughout the country.

- Funding & allocation of resources

-

Investments in PHC ensure sufficient funds are available for PHC facilities in decentralized contexts, where relevant. This helps maintain the functioning of PHC facilities, which enables them to remain open as the first point of contact with the health system.

- Medicines & supplies

-

Primary care functions cannot be of high quality if the necessary supplies are not in place to deliver care. PHC facilities and the frontline workforce must be equipped with the drugs and supplies needed to address a wide range of health needs.

- Health workforce

-

One of the core primary care functions is first-contact accessibility. The ability of a primary care health system to have first-contact access hinges on the availability of a skilled, motivated PHC workforce. Achieving comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous PHC requires a workforce that is trained to provide a broad set of services. HRH recruitment and retention strategies promote the development of a consistent, skilled, motivated workforce, supporting longitudinal care relationships between patients and providers.

Complementary elements

We define “complementary elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make an impact, whether positive or negative, on the primary care functions. However, we consider these drivers as complementary to, but not essential to performance.

- Physical infrastructure

-

Physical infrastructure that is designed to be accessible for persons with physical limitations (ex. disability, pregnancy, elderly) can help to increase the people-centeredness of care that is delivered.

- Multi-sectoral approach

-

Multisectoral action in health (ex. health in all policies) promotes comprehensiveness and coordination by engaging other services and sectors in the delivery of care. Social accountability mechanisms ensure patient involvement in decision-making and planning processes and create channels for holding governments and providers accountable.

- Adjustment to population health needs

-

Priority setting may help to ensure that the provision of PHC services is comprehensive to existing and emerging population health needs. These data are also important for defining what needs to be delivered through an essential health services package. Participatory priority setting mechanisms are one method of ensuring people-centeredness in PHC at the national level by ensuring input from communities is considered and integrated.

- Resilient facilities & services

-

Assessing the resilience of services can help promote continuity of care and continued first-contact access to PHC during times of public health emergency.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to achieve the core primary care functions can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

-

- China: WHO and China bringing people-centred care to the fore: from policy recommendations to practice

- Xiamen, China: Improving the management of NCDs through a tiered service delivery approach

- Indonesia: Puskesmas and the Road to Equity and Access

- Philippines: Delivering person-centred tuberculosis care during COVID-19 in the Philippines: improved time to TB diagnosis

- Samoa: Revitalizing PHC at the community level through Village Women’s Committees

- Solomon Islands: Strengthening coordination through role delineation policies

- Europe & Central Asia

-

- Portugal: Strengthening the delivery of integrated, continuous care across levels of care through the Portuguese National Network for Integrated Continuous Care (abridged)

- Portugal: Strengthening the delivery of integrated, continuous care across levels of care through the Portuguese National Network for Integrated Continuous Care (complete)

- Scotland: Empowering patients through the Scotland House of Care Program

- Turkey: Greater availability of PHC services results in high patient and physician satisfaction

- Tuscany, Italy: General practitioners: Between integration and co-location. The case of primary care centres

- Latin America & the Caribbean

-

- Brazil: A Community-Based Approach to Comprehensive Primary Health Care

- Chile: Achieving comprehensive PHC through intersectoral action and community engagement - Chile Crece Contingo

- Costa Rica: Promoting coordination and first contact access through regional referral networks

- Costa Rica: Building a Thriving Primary Health Care System: The Story of Costa Rica

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

-

- Ethiopia: Delivering person-centred, integrated PHC via the urban health extension professional model

- Liberia: Rebuilding PHC capacity in post-conflict settings through frontline health workers

- Liberia: Social in Innovation in Health - Last Mile Health

- Malawi: Making care more comprehensive through an integrated care management model

- Malawi: A case study about the Integrated Care Cascade in Malawi

- Mali: Removing barriers to timely PHC through proactive community care management

- Multiple regions

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on the core primary care functions and key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process.

Below, we define each of the primary care functions in greater detail:

-

First contact accessibility refers to the capacity of a primary care system to serve as the first point of contact, or a patient’s entry point to the health system, for most of a person’s health needs. It is related to inputs, access, and service availability, but reflects an individual’s behaviour of seeking care first at the primary health care level and the systemic factors that promote such behaviours.

Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” systems should act as the first point of contact for the majority of a person’s health needs throughout their life course. 21718 In a health system with primary care as the first point of contact, primary care refers (to hospital or specialists) only those problems not manageable within the primary care setting and coordinates all of the care a person receives at different care settings and levels of care (i.e. specialists). 25 This hinges on the capacity of PHC to effectively meet the majority of a person’s needs and demands (Are providers consistently available and competent? Are services high-quality and accessible?) as well as a person’s care-seeking behaviour (Where do patients seek care and why?).

First contact accessibility is related to improved technical and experiential outcomes, as well as reduced utilization of unnecessary emergency and inpatient services. 21718 While strengthening first contact accessibility is key for expanding coverage, access to care is not enough, and patients must be met by high-quality services to tangibly improve health outcomes. Because individuals are active agents in choosing when and where to access care, primary health care systems must be trusted and valued by the public as the main source of care.(105–107)

First contact access is also discussed in the organisation of services module.

-

Comprehensiveness Comprehensiveness refers to the provision of holistic and appropriate care across a broad spectrum of health problems, age ranges, and treatment modalities. Comprehensive care should address a wide range of preventive, promotive, chronic, behavioural, and rehabilitative services and include an assessment of a patient’s risks, needs, and preferences at the primary care level. refers to the provision of holistic and appropriate care across a broad spectrum of health needs, ages, and solutions. 2 89 Comprehensive primary health care is able to address a majority of promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative, chronic and palliative service needs and includes an assessment of a patient’s risks, needs, and preferences at the primary care level. 1011

-

Continuity “Continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events is experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context. Three types of continuity are considered important for high-quality PHC: (16,34,99–101)

- Relational continuity, which refers to the ongoing therapeutic relationship between a patient (and often their family) and one or more providers. True relational continuity ensures both longitudinal continuity (seeing the same provider over time) and interpersonal continuity (building a relationship of mutual trust with a single provider or care team).

- Informational continuity, which measures how well a patient’s information ‘travels’ with them throughout the health system, including over time and within and across care sites and sectors. True informational continuity ensures that all relevant patient information is available to all members of the patient’s care team (including the patient) at all encounters.

- Management continuity, which measures the extent to which providers or care teams provide seamless care within and across care sites and sectors. It can also be thought of as a consistent and coherent approach to the management of a health condition that is responsive to a patient's changing needs.

-

Coordination Coordinated care includes organizing the different elements of patient care throughout the course of treatment and across various sites of care to ensure appropriate follow-up treatment, minimize the risk of error, and prevent complications. Coordination of care happens across levels of care as well as across time, and often requires proactive outreach on the part of health care teams as well as informational continuity. refers to the health system’s ability to oversee and manage patient care over time and across levels of care. At the facility and community level, it involves the deliberate organization of between two or more people involved in a patient’s care (including the patient) to facilitate and ensure the delivery of high-quality services. It requires proactive outreach on the part of care teams and informational continuity, especially for higher-risk individuals. (4,102–104)

Effective care coordination achieves the following core functions: 4- Care teams link patients with community resources to facilitate referrals and respond to social service needs

- Care teams integrate behavioural health and speciality care into care delivery through or referral arrangements

- Care teams track and support patients when they obtain services outside the practice

- Care teams follow up with patients within a few days of an emergency room visit or hospital discharge

- Care teams communicate test results and care plans to patients and families

- Care teams provide services for high-risk patients

Continuity “Continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events are experienced as coherent and connected and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context.” Three types of continuity are considered to be important for primary care: relational continuity, informational continuity, and management continuity. and care coordination are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. Relational continuity enables care coordination because it creates the conditions and ongoing relationships needed to support seamless interactions within and across care settings or sectors. Once an enabling environment for care coordination has been established, different clinical coordination mechanisms can be used to in turn, enhance relational, management, and informational continuity of care. These mechanisms include: 16

- Sequential coordination, which refers to clinical practice interventions that support the planned handover of responsibilities and the transfer of care (i.e. use of shared EHRs, cross-sectoral plans, clinical referral pathways and processes, etc.)

- Parallel coordination, which refers to clinical practice interventions that support collaboration and communication between patients, families, and members of their care team with agreed sharing of responsibilities (i.e. use of interdisciplinary teams, individualized and tailored care plans, case and care managers, etc.)

-

People-centeredness means organising the health system around the comprehensive needs of people rather than around individual diseases. People-centeredness involves engaging with people, families, and communities as equal partners in promoting and maintaining their health—including through communication, trust, and respect for preferences as well as through ongoing education and support so that they can participate in health care decisions.(108)

is an important dimension of people-centredness. It refers to a relationship between patients and providers that is mutually respectful and trusting. Respect and trust between providers and patients can improve communication and provider motivation and contribute to the formation of continuous relationships over time. Respect and trust in a health setting should be reciprocated between patients and providers. While sometimes overlooked, patient respect for providers is a critical part of the experiential quality of care and is often influenced by patient perceptions of provider attitudes, competence, and caring behaviours. (112)

People-centeredness (including patient-provider respect and trust) is an important function for improving system performance. People-centred systems contribute to a variety of benefits for both the user and the system including improved access to care, improved health and clinical outcomes, increased health literacy, higher rates of patient satisfaction, improved job satisfaction among the health workforce, and more efficient and cost-effective services. 5562

-

- Case management is a targeted, community-based, proactive approach to care that involves case finding, assessment, care planning and coordination to integrate services to meet the needs of people with long-term conditions.

- Co-location A co-location is an approach to placing multiple services in the same physical space under a defined model outlining organizational characteristics, patient care responsibilities, coordination mechanisms, and data systems and policies. is an approach to placing multiple services in the same physical space under a defined model outlining organizational characteristics, patient care responsibilities, coordination mechanisms, and data systems and policies.

- Essential package of health services The WHO defines a service package as “a list of prioritised interventions and services across the continuum of care that should be made available to all individuals in a defined population. It may be endorsed by the government at a national or subnational level or agreed by actors where care is by a non-State actor.” : The WHO defines a service package as “a list of prioritised interventions and services across the continuum of care that should be made available to all individuals in a defined population. It may be endorsed by the government at a national or subnational level or agreed by actors where care is by a non-State actor.”

- Health care services Health care services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that health workers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that health workers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers.

- Integrated health services Health services that are managed and delivered so that people receive a continuum of health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, disease management, rehabilitation and palliative care services, coordinated across the different levels and sites of care within and beyond the health sector and according to their needs throughout the life course. : health services that are managed and delivered so that people receive a continuum of health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, disease management, rehabilitation and palliative care services, coordinated across the different levels and sites of care within and beyond the health sector and according to their needs throughout the life course.

- Patient-provider respect and trust refers to a relationship between patients and providers that is mutually respectful and trusting. Respect and trust between providers and patients can improve communication and provider motivation and contribute to the formation of continuous relationships over time.

- Longitudinal care plans A patient-centred holistic, dynamic, and integrated plan that documents disease prevention and treatment goals, plans for a patient’s future, and reflects a patient’s values and preferences - can help to facilitate management continuity and coordinated care. shared longitudinal care plans - a patient-centred holistic, dynamic, and integrated plan that documents disease prevention and treatment goals, plans for a patient’s future, and reflects a patient’s values and preferences - can help to facilitate management continuity and coordinated care. (34,110)

- The 3-in-1 principle The 3-in-1 principle reorients facilities toward a common goal: “one-system-one population-one pot of resources”. Highly developed networks offer a broad continuum of care across all service lines, enabled through information technology (eHealth) tools. reorients facilities toward a common goal: “one-system-one population-one pot of resources”. Highly developed networks offer a broad continuum of care across all service lines, enabled through information technology (eHealth) tools. 30

- Vertical integration Vertical integration redefines the role and interactions among primary, secondary, and tertiary facilities. Most initiatives in vertical integration are conceptualized in terms of referral systems. redefines the role and interactions among primary, secondary, and tertiary facilities. Most initiatives in vertical integration are conceptualized in terms of referral systems. (111)

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

References:

- Doherty J. The Cost-Effectiveness of Primary Care Services in Developing Countries: A.

- Rao M, Pilot E. The missing link--the role of primary care in global health. Glob Health Action. 2014 Feb 13;7:23693.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Care Coordination [Internet]. [cited 2018 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/coordination/index.html

- Thomas-Hemak L. Closing the loop with referral management. Group Health Research Institute; 2013.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502.

- Phillips C. Care coordination for primary care practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016 Nov 12;29(6):649–51.

- WHO. Primary health care measurement framework and indicators: monitoring health systems through a primary health care lens [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240044210

- WHO. Primary Health Care Transforming Vision into Action: Operational Framework. World Health Organization; 2018.

- Bitton A, Veillard JH, Basu L, Ratcliffe HL, Schwarz D, Hirschhorn LR. The 5S-5M-5C schematic: transforming primary care inputs to outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018 Oct 2;3(Suppl 3):e001020.

- Glassman, Regan, Chi, Chalkidou. Getting to Convergence: How “Vertical” Health Programs Add Up to A Health System | [Internet]. Center for Global Development | Ideas to Action. 2020 [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/getting-convergence-how-vertical-health-programs-add-health-system

- PHCPI. Leveraging “vertical” health investments for PHC. PHCPI; 2015.

- The Maximizing Positive Synergies Academic Consortium. Interactions between global health initiatives and health systems. 2009.

- Magnussen L, Ehiri J, Jolly P. Comprehensive versus selective primary health care: lessons for global health policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004 Jun;23(3):167–76.

- WHO, UNICEF. Internal working draft: Primary health care performance: measurement for improvement- technical specifications. WHO; 2021 Oct.

- Armstrong, M. & Baron, A. (1998), Performance Management Handbook, IPM, London [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jan 30]. Available from: http://www.sciepub.com/reference/151290

- WHO. Continuity and coordination of care. WHO; 2018.

- Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too Far To Walk: Maternal Mortality in Context. Sm Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–110.

- Donaldson M, Yordy K, Vanselow N. Defining Primary Care: an Interim Report. National Academies Press (US); 1994.

- PHCPI. Primary Health Care Progression Model Assessment Tool [Internet]. Primary Health Care Progression Model Assessment Tool. 2019. Available from: https://improvingphc.org/sites/default/files/PHC-Progression%20Model%202019-04-04_FINAL.pdf

- WHO. Quality and accreditation in health care services: a global review. 2003 [cited 2020 May 29]; Available from: https://www.who.int/hrh/documents/en/quality_accreditation.pdf

- Tarantino L, Laird K, Ottosson A, Frescas R, et al. Institutional Roles and Relationships Governing the Quality of Health Care. Bethesda, MD: Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates and USAID Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems Project, URC; 2016 Aug.

- WHO. Handbook for national quality policy and strategy: a practical approach for developing policy and strategy to improve quality of care. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Health Care Services, Board on Global Health, Committee on Improving the Quality of Health Care Globally. Crossing the global quality chasm: improving health care worldwide. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018.

- Mbindyo R, Kioko J, Siyoi F, Cheruiyot S, Wangai M, Onsongo J, et al. Legal and institutional foundations for universal health coverage, Kenya. Bull World Health Organ. 2020 Oct 1;98(10):706–18.

- Rowe AK, Rowe SY, Peters DH, Holloway KA, Chalker J, Ross-Degnan D. Effectiveness of strategies to improve health-care provider practices in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Nov;6(11):e1163–75.

- Christensen T. The Evolution of Patient-Centered Care and the Meaning of Co-Design [Internet]. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2017 [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/evolution-of-patient-centered-care-and-the-meaning-of-co-design

- Colleaga. Co-design and Patient-centred Design [Internet]. Colleaga. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.colleaga.org/article/co-design-and-patient-centred-design

- Bitton A, Pesec M, Benotti E, Ratcliffe H, Lewis T, Hirschhorn L, et al. Shaping tiered health care delivery system in accordance with People-Centered Integrated Care Model. Deepening Health Reform in China : Building High-Quality and Value-Based Service Delivery. World Bank Group; 2016.

- Schottenfeld, Petersen, Peikes, Ricciardi, Burak, McNellis, et al. Creating Patient-Centered Team-Based Primary Care. AHRQ. 2016;

- World Bank. Deepening Health Reform in China: Building High-Quality And Value-Based Service Delivery. World Bank Group, World Health Organization; 2016.

- Glassman, Keller J, Lu J. Realizing the Promise of Primary Health Care and Avoiding the Pitfalls in Making Vision Reality.

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Nov;6(11):e1196–252.

- Lewis T, Synowiec C, Lagomarsino G, Schweitzer J. E-health in low- and middle-income countries: findings from the Center for Health Market Innovations. Bull World Health Organ. 2012 May 1;90(5):332–40.

- Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003 Nov 22;327(7425):1219–21.

- Romano MJ, Segal JB, Pollack CE. The association between continuity of care and the overuse of medical procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Jul;175(7):1148–54.

- Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005 Apr;3(2):159–66.

- WHO. Draft road map for access to medicines, vaccines and other health products, 2019 – 2023. World Health Organization; 2018.

- 38. LeWine HE. Millions of adults skip medications due to their high cost - Harvard Health [Internet]. Harvard Health Publishing - Harvard Medical School. 2015 [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/millions-skip-medications-due-to-their-high-cost-201501307673

- HIMSS. What is Interoperability? | HIMSS [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.himss.org/library/interoperability-standards/what-is-interoperability

- Enabulele O, Enabulele JE. A look at the two–way referral system: experience and perception of its handling by medical consultants/specialists among private medical practitioners in Nigeria. International Journal of Family & Community Medicine. 2018;

- Sohrabi M-R, Albalushi RM. Clients’ satisfaction with primary health care in Tehran: A cross-sectional study on Iranian Health Centers. J Res Med Sci. 2011 Jun;16(6):756–62.

- Assis MMA, do Nascimento MAA, Pereira MJB, de Cerqueira EM. Comprehensive health care: dilemmas and challenges in nursing. Rev Bras Enferm. 2015 Apr;68(2):304–9, 333.

- Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970-1998. Health Serv Res. 2003 Jun;38(3):831–65.

- WHO. WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Garimella S, Sheikh K. Health worker posting and transfer at primary level in Tamil Nadu: Governance of a complex health system function. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016 Sep;5(3):663–71.

- Mbemba GIC, Gagnon M-P, Hamelin-Brabant L. Factors influencing recruitment and retention of healthcare workers in rural and remote areas in developed and developing countries: an overview. J Public Health Africa. 2016 Dec 31;7(2):565.

- WHO & UNICEF. A Vision for Primary Health Care in the 21st Century: towards universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. . World Health Organization; 2018.

- UpToDate. Hospital discharge and readmission [Internet]. UpToDate. 2022 [cited 2022 May 31]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hospital-discharge-and-readmission

- Jakucs C. Discharge planning starts at admission [Internet]. NURSE.com. 2021 [cited 2022 May 31]. Available from: https://resources.nurse.com/discharge-planning-starts-admission