|

|

|

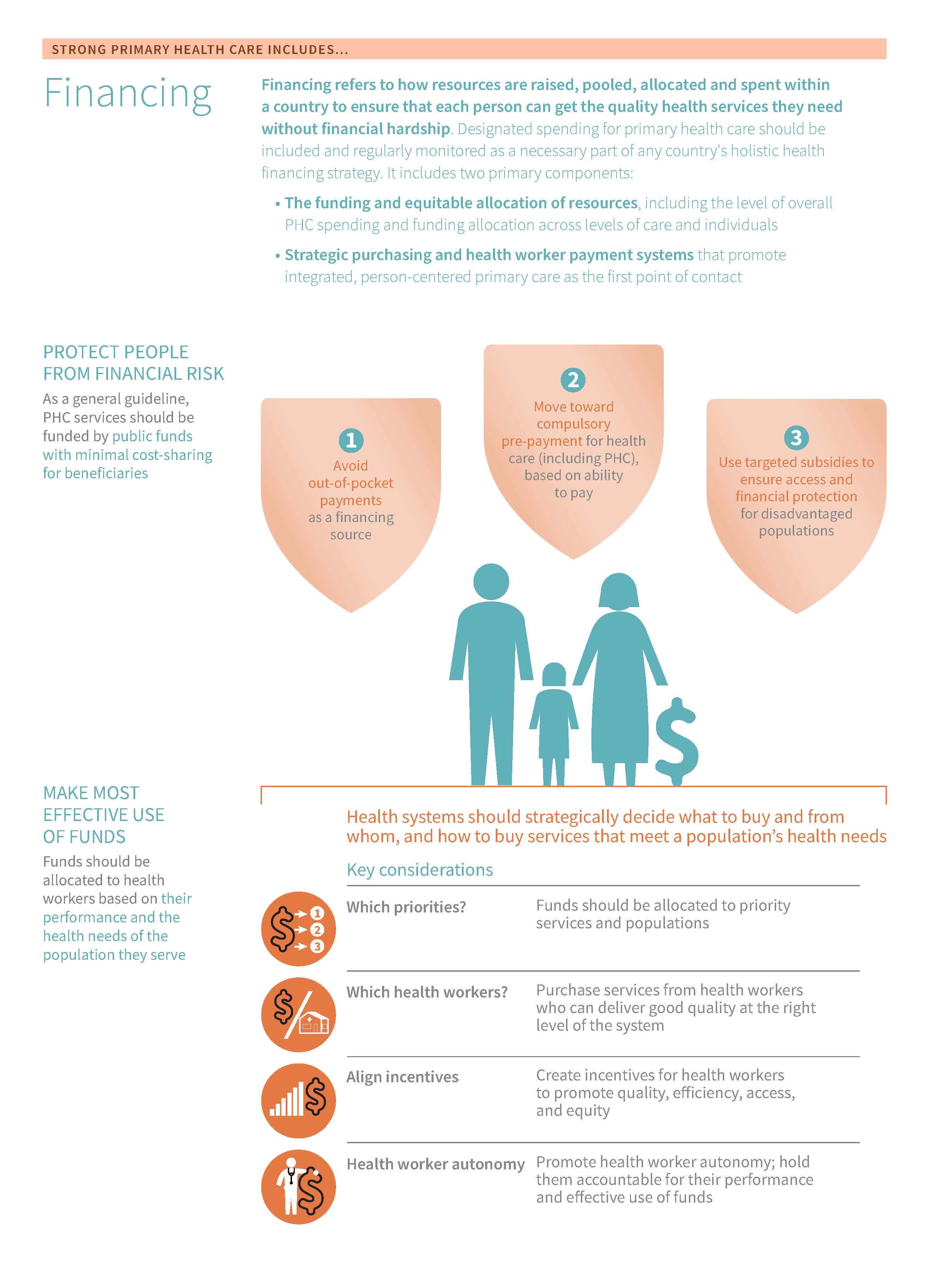

Funding and allocation of resources includes examining the level of PHC spending based on national health accounts – including funding sources – as well as funding allocation across different levels of care (from primary care to hospitals) and public health interventions

The effective use of funds enables health systems to direct resources to providers and services in response to a population’s health needs. The availability of funds and how funds reach facilities can shape the supply, accessibility, and quality of services, resulting in flexibility or constraints for primary care providers.

PHC spending includes expenditures on “first-contact” curative and preventive primary care – sometimes provided at different levels of the health system, and by a variety of different health workers depending on a country's context – as well as community outreach and public health strategies that prevent illness and promote well-being. It includes examining the level of PHC spending based on national health accounts – including funding sources – as well as funding allocation across different levels of care (from primary care to hospitals) and public health interventions.

The availability of funds and how funds reach facilities can shape the supply, accessibility, and quality of services, resulting in flexibility or constraints for primary care providers. Facility managers’ ability to Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. , manage and track funds at the facility level can impact health care providers' ability to be responsive to changing disease burdens and patient needs.

This funding and allocation of resources module will explore the availability and management of funds at the facility level, a range of Public financial management The rules and regulations established to ensure transparent, effective, accountable management of public (government) finances. PFM includes all phases of the budget cycle, including the preparation of the budget, budget execution, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangements, and external audit. processes such as budget formation and execution, and how facilities that receive government funding, or a mix of government and private funding, manage facility operations and provide health services.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Read on to learn how to use country data to:

- Make informed decisions about where to spend time and resources

- Track progress and communicate these updates to constituents or funders

- Gain new insights into long-standing trends or surprising gaps

Countries can measure their performance using the Vital Signs Profile (VSP). The VSP is a first-of-its-kind tool that helps stakeholders quickly diagnose the main strengths and weaknesses of primary health care in their country in a rigorous, standardized way. The second-generation Vital Signs Profile measures the essential elements of PHC across three main pillars: Capacity, Performance, and Impact. Funding & allocation of resources is measured in the Financing domain of the VSP (Capacity Pillar).

If a country does not have a VSP, it can begin to focus improvement efforts using the subsections below, which address:

- Key indications

-

If your country does not have a VSP, the indications below may help you to start to identify whether funding & allocation of resources is a relevant area for improvement:

- Inefficiencies and/or leakages in the budget transfer system: if there are leakages or inefficiencies in the budget transfer system, this can result in a very small percentage of the health sector budget actually reaching primary care facilities resulting in facilities having minimal funding available to meet operational costs such as budgets for outreach services and communities

- Basing budget allocation on historical spending levels: if budget allocation for primary care facilities is based on historical spending levels rather than allocating based on facility needs, this points to challenges in health budget formulation processes at the national level (i.e. variability in annual amounts allocated to the health sector, weak evidence on actual costs etc.) and/or poor facility-level financial management of such budgets

- Facility managers and staff lack training: if there is a lack of training for facility managers and/or staff when it comes to financial management and disbursement, this can lead to issues of absenteeism and workforce shortages. Training on how to hire and fire staff locally, pay staff on time, and adjust quantities of medicines and other supplies based on local needs are all examples of the type of financial management and disbursement experience that may be lacking.

- Facilities lack information systems: if there are no financial management information systems in place, then facilities will face challenges when it comes to their ability to track and manage funds

- Fund generation: a general inability to generate sufficient funds for health and/or the lack of reliance on public or compulsory sources to generate these funds are both indications that the funding and allocation of resources for the health sector can be improved upon

- Key outcomes and impact

-

Countries that strengthen their funding & allocation of resources may achieve the following benefits or outcomes:

- Responsiveness: appropriate allocation and funding for PHC at the national and sub-national levels is vital and must be adapted according to the needs of the population. For example, through mechanisms such as need-based budgeting and re-allocated funds where they are needed most. Additionally, facility managers’ ability to effectively budget, manage and track funds at the facility level can impact health care providers' ability to be responsive to changing disease burdens and patient needs.

- Financial protection: effectively funded PHC services (e.g. working to fund services with public funds) helps to minimize cost-sharing and prevent catastrophic spending for beneficiaries. Ensuring that governments are moving towards greater reliance on compulsory sources to fund PHC is critical as this can increase access to health services and improve financial protection for the population as a whole. A deep understanding of the various sources funding a country’s health system is key in promoting financial protection.

- Quality, accessibility and supply of PHC services: the adequate supply and quality of PHC services are highly dependent on a country’s ability to allocate and manage funds appropriately as well as each health facility’s availability of funds. The availability of these funds and how they reach facilities can shape the supply, quality and accessibility of services, resulting in flexibility or constraints for primary care providers throughout a country’s health system.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Explore this page for a curated list of actions to improve the funding & allocation of resources, which embark on:

- An explanation of why the action is important for improving the funding & allocation of resources

- Descriptions of activities or interventions countries can implement to improve funding & allocation of resources

- Descriptions of the key drivers in the health system that should be improved to maximise the success or impact of actions

- Relevant tools and resources

Key actions:

-

To allocate enough funding to PHC as well as effectively track PHC funding, countries first have to raise enough revenues for health overall. But in many low- and middle-income countries, raising enough money for health remains challenging. Generating more health funding from domestic sources is increasingly important given uncertainty about continued funding from international donors.

Key activities

Health systems level

- Demonstrate the efficiency of PHC: in order to help make the case for allocations to PHC, health sector leaders can demonstrate the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and impact of PHC. There is evidence that increased investment in primary care can reduce the use of secondary care and reduce overall health costs.2223 Effective primary care can reduce the total number of hospitalizations, including avoidable admissions and emergency admissions24

- Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. : A systematic priority-setting process driven by data on health needs and population preferences, with explicit decision-making criteria that include cost-effectiveness and disease burden as well as equity, is most likely to maximize health benefits given finite resources (see Multi-sectoral Approach module). In addition, PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. are highly cost-effective, so such systematic processes are likely to prioritize coverage of PHC benefits. Switching from current practice to covering more cost-effective services can lead to substantial health gains without an increase in spending, and actually free up resources that can be further invested in PHC.2526

- Explicit health policies that call out PHC: Health financing and benefits policies should make explicit which PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. will be covered by government funds, who is entitled to that coverage, and where and how services will be provided.25 Useful policy instruments for defining which benefits will be funded by the government25 include creating essential medicines lists27; defining health benefit plans28; and establishing a health technology assessment process.

- Civil society organizations: public health funding and health-promotive spending in other sectors can easily remain invisible to political constituencies and decision-makers, especially in contrast to “visible” spending on disease priorities. Civil society organizations can play a critical role in advocating for spending on these less-visible but still very essential efforts. Learn more about the role of civil society organizations in the Multi-Sectoral Approach module.

- Amplify evidence-based conclusions: evidence shows that higher spending on public health areas is associated with lower population-level mortality and morbidity rates.4 Similarly, evidence also confirms that outpatient and community-based delivery of primary care is more cost-effective compared to inpatient or emergency department delivery of primary care services.5 Promoting these evidence-based conclusions is an effective way to garner support for more revenue for PHC.

- Greater reliance on compulsory funding sources: governments should aim to move towards greater reliance on public (compulsory) sources of funding for health, as evidence shows this increases access to health services and improves for the population2

District level

- Priority setting The process of making decisions about how best to allocate limited resources to improve population health. : at the district level, health system managers should also set priorities for financing PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. as part of a broader system-wide priority-setting process, as described above. A transparent, inclusive process for defining this list of priority services is important for political buy-in and sustainability over time.26

Guiding questions

HOW MUCH IS THE COUNTRY SPENDING ON HEALTH OVERALL? DOES THE COUNTRY NEED TO INCREASE SPENDING ON HEALTH CARE IN GENERAL?

To enable increased allocations to PHC, the most important first step may be increasing overall funding for health through (including improved tax collection) and improvements to efficiency29, relying mainly on public funds. Government revenues for health can be mobilized in various ways, including through income taxes, payroll taxes, consumption taxes, import duties, and taxes on natural resources.2

HOW MUCH OF CURRENT HEALTH EXPENDITURE IS SPENT ON PHC (PRIMARY CARE SERVICES AND PUBLIC HEALTH INTERVENTIONS), COMPARED TO SECONDARY OR TERTIARY MEDICAL SERVICES?

Spending on PHC makes sense because it is a “best buy” for the health sector – maximizing health outcomes for the population given finite resources.6 Health spending should be tracked systematically using the System of Health Accounts 2011 The System of Health Accounts (SHA) 2011 is a methodology for tracking all health spending in a country. It generates consistent and comprehensive data on the magnitude of health spending, disaggregated by the sources of financing, financing schemes that manage health spending, the kinds of health care goods and services consumed and the health care providers who deliver these goods and services. methodology19, and the WHO’s recently-developed approach to tracking PHC spending in particular.13 Health system leaders can use resource-tracking data to advocate for greater allocations to PHC.

WHAT ARE THE PRIMARY SOURCES OF FUNDING FOR HEALTH AND FOR PHC IN PARTICULAR, AND HOW MUCH COMES FROM HOUSEHOLDS’ OUT-OF-POCKET SPENDING, GOVERNMENT BUDGET, OR DONORS?

To ensure sustainable financing for PHC and promote financial protection, it is important to understand the sources of funding for the health system. Numerous low-income countries rely heavily on donor funding. Countries that face declining donor support will increasingly need to determine how to allocate enough funds for PHC using domestic public resources. It is also important to reduce reliance on household out-of-pocket spending as a source of health financing, as it reduces financial access to care and increases the risk of impoverishment.

WHAT TYPE OF SUPPLY-SIDE INVESTMENTS SHOULD BE MADE TO PROMOTE PHC?

Encouraging greater use of primary care services by making services free or more affordable can only improve health outcomes if there is adequate infrastructure, a supply of capable health workers, and sufficient medicines and supplies to absorb the increased demand. Policymakers should conduct subnational analyses to inform where there are critical gaps in service provision capacity, and needed funding should be allocated to strengthen that capacity.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Primary care Primary care is “a key process in the health system that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated patient-focused care.” functions

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Population health management

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2016: Budgeting for Health

- Center for Global Development, 2017: Designing Benefits for Universal Health Coverage

- WHO, 2021: Essential Medicines List

- Joint Learning Network, 2018: Designing Health Benefit Plans

- IDSI, 2018: Health Technology Assessment

-

Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. preparation exercises help facilities estimate how much funding they will have available and how they will use that funding. In larger PHC facilities with authority to manage their own finances, budget preparation is an essential component of planning (such as what kinds and how many medicines and supplies to buy, which staff to hire, and how to meet the evolving needs of the patients and communities the facility serves)

Key activities

Health systems level

- Allocate appropriately for PHC: while there is no global standard for the "right" percentage of total health spending to allocate to primary health care, evidence shows that low-income countries should aim to invest $65 per capita and upper-middle income countries should aim to invest $334 (2014 dollars) per capita based on estimated investment needs in order to facilitate delivery of a core set of preventive and outpatient PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. (*recurrent costs only).18

- Needs-based budgeting: oftentimes budgets are set based on historical spending of a given health facility, in order to improve how budgets are it’s best to set them based on needs as opposed to basing them on historical spending at these facilities. Health sector budget allocations should be set utilizing need-based, empirical evidence, including population size, demographic characteristics like age and fertility rates, and the burden of disease and associated treatment costs.

- Using output-based budgeting: output-based budgeting is also known as “performance budgeting”, “performance-based budgeting”, “” and “budgeting for results” and is a kind of budgeting that is oriented around achieving specific results and anticipating the resources needed to achieve those results. This type of budget orientation can help hold facilities accountable for delivering outputs (such as successful prevention, diagnosis and treatment of patient conditions), rather than simply spending inputs. This type of budgeting helps to illustrate what will be accomplished with the money being spent as opposed to showing that it was spent on what was intended in the first place. Additionally, utilizing output-based budgeting can often improve the responsiveness of budgets to changing local health needs. Appropriate use of output-based budgeting can result in an increase in the responsiveness of budgets to changing local health needs and adjustment to population health needs303132

- and : countries can improve the budgeting process by moving to a combination of top-down (where the central budgeting authority determines resource allocations based on revenues available) and bottom-up budgeting (where facilities estimate the budget needed to meet local service delivery needs).

- Benefit incidence analysis: Easy-to-understand allocation formulas with a system of financial transfers for poorer areas are recommended.10 Countries can use benefit incidence analysis to understand how much poor areas benefit from government spending, relative to wealthier groups, and this can assist in developing evidence-based allocation criteria.12 (For further reading on benefit incidence analysis and when it can be utilized, see How to do (or not to do) a benefit incidence analysis.)

- Improve central level budget execution: countries that use cash budgeting processes (meaning cash must be available before the budget is disbursed) often experience unpredictable availability of funds. If the central budget is unrealistic due to limited cash at hand, Ministries of Finance often engage in cash rationing. Disbursement of funds and staff remuneration can be delayed for many months due to liquidity problems and then is often disbursed in larger sums towards the end of the fiscal year.11 Improvements in timely, regular health worker payments are likely to require budget process strengthening and improvement in budget execution at the central level.

Guiding questions

WHAT PERCENTAGE OF THE HEALTH BUDGET REACHES PRIMARY CARE FACILITIES?

In many contexts, only a small percentage of the overall health sector budget reaches primary care facilities. Facilities often have little funding available to meet operational costs aside from health worker salaries, including budgets for outreach services in communities. Understanding the percentage of funding reaching facilities is the first step in diagnosing potential challenges and working towards improvement. A public expenditure tracking survey can unpack how funding flows through the health system, what percentage of funds reach frontline providers, and potential sources of inefficiencies and/or leakages.

HOW ARE FUNDS ALLOCATED ACROSS PRIMARY CARE FACILITIES?

Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. allocation for primary care facilities should be need-based, rather than based on historical spending levels. Many countries have adopted resource allocation formulas that combine population size, disease burden, poverty, and other equity indicators relevant to the context (see Building Strong Public Financial Management Systems Towards Universal Health Coverage for country examples). Others have tied resource allocations to the utilization of priority services (see Argentina case study).

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Population health management

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2016: Budgeting for Health

- The World Bank, 2014: Results-based financing

- Health Policy & Planning, 2011: How-To: Benefit Incidence Analysis

- RBF Health, 2010: Results-Based Financing for Health (RBF): What’s All the Fuss About?

-

Strong financial management systems allow facilities and the health system overall to manage and track funds effectively, comparing spending to estimated budget allocations and adjusting as needed. They also help identify when underperformance is due to inefficiency or insufficient funding and plan for future spending needs. Additionally, appropriate tracking of PHC funds and resources for PHC are critical in effectively funding PHC.

Sub-action 1. Promote provider autonomy

Key activities

Health systems level

- Ensure accountability systems are in place: systems with increased provider autonomy and health system managers must also employ new or strengthened accountability systems to ensure that facilities are utilizing funds for their intended purpose.32 Improved record keeping at the facility level can increase the accuracy of public expenditure tracking surveys, which can be utilized to monitor improvements in funding flows to facilities over time.

- Provide training and financial management guidelines: in order to effectively manage facility budgets, managers must have the capacity to engage in proactive planning and forecasting and to account for and report on expenditures incurred at the facility level. Health system leaders should provide training and guidelines to support facility managers in the forecasting and reporting processes. While provider autonomy is important, facilities still require high-level guidance on how best to utilize funds.

Facility level

- Support provider autonomy: “Provider autonomy” refers to the extent to which frontline facility managers have the authority to function as funds managers and to change the mix of inputs and services they provide based on their patients’ needs (e.g. to respond to an unexpected outbreak of disease or to adapt to a change in drug pricing). When health facilities have strong financial management capacity and authority to make some financial management decisions, they are more likely to adjust service provision and deploy inputs based on the needs of the population.12 Increasing provider autonomy often requires reforms to a country’s PFM regulations (see above).32

- Dispersing smaller cash incomes: budget officials may consider disbursing some cash income directly to primary care facilities, rather than only in-kind inputs. This can provide facility managers more flexibility to reallocate funds as needed. Similar “” interventions, where cash funds are directly transferred to primary care facilities and they are granted autonomy in the planning, management, and use of those funds to improve service delivery, are underway in Kenya33 and Tanzania34.

- Procuring small amounts of medicines & supplies: recognizing that most medicines and supplies will be bulk-procured centrally, allowing facilities to procure small amounts of medicines and supplies with their funds may reduce both wastage and stock-outs and improve responsiveness to short-term local needs.

- Facility bank accounts: establishing facility bank accounts and making direct payments to facilities can more efficiently move funds to front-line providers. Facility bank accounts can also help expedite disbursements and increase budget execution rates. However, this will require increasing facilities’ financial management capacities to manage, track, and report on funds provided. Additionally, allowing facilities to receive cash income and open bank accounts may require changing their legal status; this can be a serious bottleneck in some contexts.

Sub-action 2. Improve public financial management systems

Key activities

Health systems level

- Reform (PFM) regulations: PFM regulations aim to promote transparent, effective, accountable management of government finances.10 They touch upon all phases of the budget cycle, including the preparation of the budget, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangements, and external audit. However, some PFM rules – intended to ensure predictability of spending and careful fiscal control -- can create inefficiencies in the health sector, where health care needs are unpredictable and quick responses to crises are essential. Changes to PFM regulations may be needed to increase the authority of lower-level spending units (including health facilities) to flexibly move funds across budget lines. This can improve PHC performance by enabling facilities to respond to changes in population needs and provider payment incentives more nimbly.10 In general, these changes should be integrated into broader health system reforms35, including but not limited to primary care, and must be closely coordinated by the Ministry of Finance.

- Align PFM regulations to how facilities are actively receiving funds: ensuring alignment between how facilities actually receive funds and the public financial management regulations on how funds are used and accounted for is critically important. In many countries, the beneficial impacts of provider payment reforms (see the Financing module) have been muted by a lack of provider autonomy to allocate funds at the facility level, sometimes due to strict PFM rules. At the primary level, greater provider autonomy has sometimes been introduced through performance-based or results-based financing programs (discussed above)36

- Track expenditure in a standard manner: ensuring that PHC expenditure is being tracked in a standard manner is a critical first step to understanding variations in PHC performance and health outcomes as well as determining where efforts can be made to improve performance.13 Tracking levels and trends in PHC spending is essential for advocating for increased investments in PHC and creating buy-in in general. Additionally, tracking PHC spending can also help health system managers identify regions, populations, or health conditions that are underfunded.

- Simplify allocation systems: simplifying funds’ allocation systems by reducing the number of layers through which disbursements must flow can increase the timeliness of payments and reduce leakages. Successful budget execution entails coordinating and streamlining the processes that lead to effective funds transfers from the national treasury to the Ministry of Health and then to districts and health providers.

- Financial information systems: adequate financial management information systems are essential to track expenditures and report on cash income.

Facility level

- Financial management Systems and processes at the facility level to track revenues and expenditures, ensure that resources are not wasted, and ensure that desired results are achieved training: training in the management of a cash book can support day-to-day expenditure management at smaller health facilities, while larger facilities often require dedicated accounting and/or financial management staff.32 In larger facilities, managers should have the capacity to develop and negotiate facility business plans to guide spending.

Guiding questions

WHAT IS THE CAPACITY OF FRONTLINE MANAGERS TO MANAGE FUNDS EFFECTIVELY AT THE FACILITY LEVEL?

Introducing some provider autonomy allows providers to be responsive to changing patient needs by changing inputs used or the mix of services provided, increasing efficiency and improving responsiveness to patient needs. Depending on the country’s provider payment systems, increasing provider autonomy may also be required to ensure providers can respond to appropriate incentives to improve efficiency and increase quality (see Health Financing strategy).

This may require building greater capacity for financial management at the facility level. Completing a diagnostic of providers’ capacity for financial management can inform policy-making on whether and how to increase providers’ autonomy. Policymakers will need to understand existing financial management systems, human resource capacities (both skills and workload), current management practices for facility-generated revenues, and facilities’ forecasting abilities. Public financial management The rules and regulations established to ensure transparent, effective, accountable management of public (government) finances. PFM includes all phases of the budget cycle, including the preparation of the budget, budget execution, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangements, and external audit. guidelines must also be revised to enable facilities legally to open their own bank accounts and keep internally generated revenues for use at the facility.

Related elements

- Policy & leadership

- Organisation of services

- Adjustment to population health needs

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Purchasing & payment systems

- Population health management

Relevant tools & resources

- WHO, 2019: Leveraging Public Financial Management for Better Health in Africa

- Biomed Central, 2019: Understanding the implementation of Direct Health Facility Financing and its effect on health system performance in Tanzania

- WHO, 2017: Aligning public financial management and health financing

- The World Bank, 2011: Financial Management Information Systems - What Works

- Health Policy & Planning, 2010: Direct facility funding as a response to user fee reduction

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Understanding and identifying the drivers of health systems performance--referred to here as “related elements”--is an integral part of improvement efforts. We define related elements as the factors in a health system that have the potential to impact, whether positive or negative, the funding & allocation of resources. Explore this section to learn about the different elements in a health system that should be improved or prioritized to maximize the success of actions described in the “take action” section.

While there are many complex factors in a health system that can impact the funding & allocation of resources, some of the major drivers are listed below. To aid in the prioritization process, we group the ‘related elements’ into:

Upstream elements

We define “upstream elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make the biggest impact, whether positive or negative, on service quality.

- Policy & leadership

-

PHC policies establish financing and expenditure plans and processes. PHC policies should include costed service packages and holistic strategies, including accounting for social determinants of health. For more information on what strong policy and leadership for PHC looks like, visit the Policy & Leadership module.

- Adjustment to population health needs

-

Participatory and data-based priority setting should determine how to allocate limited resources to PHC. For more information on what effective adjustment to population health needs for PHC looks like, visit the Adjustment to Population Health Needs module.

Complementary elements

We define “complementary elements” as the factors in a health system that have the potential to make an impact, whether positive or negative, on service quality. However, we consider these drivers as complementary to, but not essential to performance.

- Multi-sectoral approach

-

Social accountability mechanisms can support monitoring of PHC spending and hold stakeholders accountable to commitments. For more information on what a strong multi-sectoral approach looks like, visit the Multi-sectoral Approach module.

- Purchasing & payment systems

-

Purchasing & Payment systems are often related to the funding and allocation of resources to PHC, however, the direction of influence is circumstantial and often complementary. For more information on what effective purchasing and payment systems look like, visit the Purchasing & Payment Systems module.

- Population health management

-

Participatory and evidence-based local priority setting should determine how to allocate limited resources to PHC at the sub-national level. For more information on what effective population health management for PHC looks like, visit the Population Health Management module.

- Efficiency

-

Making health spending more efficient is one way of expanding the fiscal space for health. By increasing efficiency, limited resources can go further, opening up funding for health sector priorities such as PHC. In addition, demonstrating the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and impact of PHC helps to make the case for budget allocations to PHC. For more information on what strong efficiency for PHC looks like, visit the Service Quality module.

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Countries seeking to improve the funding & allocation of resources can pursue a wide array of potential improvement pathways. The short case studies below highlight promising and innovative approaches that countries around the world have taken to improve.

PHCPI-authored cases were developed via an examination of the existing literature. Some also feature key learnings from in-country experts.

- East Asia & the Pacific

- Europe & Central Asia

- Latin America & the Caribbean

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South Asia

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

Building consensus on what strong funding & allocation of resources means and the key strategies to fix gaps is an important step in the improvement process.

Below, we define some of the core characteristics of funding & allocation of resources in greater detail:

-

To allocate enough funding to PHC, countries first have to raise enough revenues for health overall. But in many low- and middle-income countries, raising enough money for health remains challenging. Generating more health funding from domestic sources is increasingly important given uncertainty about continued funding from international donors.

for health

Resource mobilization strategies vary across countries; most countries usually consider a mix of domestic funding sources for the health system.1 Domestic resources for health can come from compulsory payments (such as consumption or income taxes, or public insurance contributions like payroll taxes) or private voluntary payments (by employers and businesses, private foundations, voluntary health insurance payments, or household out-of-pocket spending). Relying on a mix of funding sources can help countries weather economic and political cycles. However, governments should aim to move towards greater reliance on public (compulsory) sources of funding for health, as evidence shows this increases access to health services and improves for the population.2

Making health spending more efficient is another way of expanding -- the budgetary room that allows a government to spend on public purposes without undermining fiscal sustainability3. By increasing efficiency, limited resources can go further, opening up funding for health sector priorities such as PHC. Providing evidence of more efficient spending on health services can also help health sector leaders make the case with legislators for greater investment in the health system2. See the Purchasing and Payment Systems module for how strategic health purchasing can increase efficiency.

Making the case for PHC funding: Efficiency Efficiency refers to the ability of a health system to attain its desired objectives with the available resources, while minimising waste and maximising capacities to deliver care to those who need it. , cost-effectiveness, and impact

Evidence shows that higher spending on public health areas is associated with lower population-level mortality and morbidity rates.4 Likewise, a review of the evidence also confirms that outpatient and community-based delivery of primary care is more cost-effective compared to inpatient or emergency department delivery of primary care services.5 Promoting these evidence-based conclusions is an effective way to garner support for more revenue for PHC.

Conversely, an emphasis on hospital-based service delivery can lead to escalating health care expenditures without leading to better population health outcomes. Historically, many countries have allocated the bulk of funding to secondary and tertiary hospitals in urban areas, while underinvesting in primary care.3 This can occur when national health strategies emphasize delivery of disease control programs through hospitals6 or emphasize curative hospital care at the expense of less visible, less politically popular public health endeavours. It can also occur when provider payment methods incentivize facilities to deliver more expensive, complex care than may be needed.

Defining guaranteed PHC benefits

Guaranteeing access to a defined PHC benefit package can help ensure that spending on PHC is prioritized. Since “[n]o country, no matter how rich, is able to provide its entire population with every technology or intervention that may improve health or prolong life”7, countries cannot guarantee coverage for all diseases and treatments. But because primary health care is highly cost-effective and prevents many minor conditions from becoming more serious and expensive conditions, it is important to promote access to PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. by ensuring that families have coverage for PHC-related costs.3

“ Earmarking Earmarking means ring-fencing, or protecting, all or a portion of a tax or other revenue source for a particular purpose, such as a specific health program or service. ” funds for PHC

Earmarking Earmarking means ring-fencing, or protecting, all or a portion of a tax or other revenue source for a particular purpose, such as a specific health program or service. for health is when a specific revenue source or a protected expenditure stream is dedicated to health.8 For instance, revenues from a tax on tobacco might be allocated to a national health insurance scheme. Earmarked revenues may bring additional resources for priority programs and can protect those priorities from changing political preferences. However, some caution should be used when deciding to earmark funds for health or PHC. Earmarking Earmarking means ring-fencing, or protecting, all or a portion of a tax or other revenue source for a particular purpose, such as a specific health program or service. can create rigidities in the that can be inflexible to shifting government priorities. Earmarked funds can be susceptible to “capture” by special interests, and can be economically distortive since earmarks are typically funded through a consumption or payroll tax.8 Also, over time any increased revenues from the earmarked source may be offset by other budget reductions, resulting in little if any increase in total public funding available.8 Decisions about earmarking funds for PHC should be considered relative to each country’s political context.

-

Facility refers to systems and processes at the health facility level to track and manage revenues (funds received from government transfers, insurance payments, and patient fees) and expenditures (outlays on personnel and other inputs). Strong financial management systems allow facilities and the health system overall to manage and track funds effectively, comparing spending to estimated budget allocations and adjusting as needed. They also help identify when underperformance is due to inefficiency or insufficient funding and plan for future spending needs.

Common components that health facilities need to manage include personnel remuneration, operations, and capital spending.

- Personnel remuneration includes staff salaries and fringe benefits. Staff who are government employees may be hired and paid directly by the central or subnational government. Sometimes the civil service is entirely administered by another ministry outside the health sector – for example, a Ministry of Finance – and their costs will not be handled by the facility at all. In some contexts, health facility managers can hire additional contract staff to cover for staff shortages or fill specific positions (e.g. laboratory services). These costs would be managed directly by the facility.

- Operations include the non-personnel inputs required to run the facility and can include:

- Medicines, supplies and equipment. These are either procured centrally and distributed in-kind, or facilities may receive funds directly and manage their own procurement.

- Community outreach activities. These would include allocations for vehicles and fuel costs, educational supplies, etc.

- Maintenance, utilities, and sanitation.

- Capital spending includes infrastructure improvements. These may also be managed centrally, sometimes by a separate public works ministry.

Challenges with facility financial management

Many primary care facilities have only limited authority to manage their own funds. They may not have a facility bank account that they can access directly; their staff may be managed and paid centrally and they may have little ability to hire and fire staff locally. Medicines and supplies may be provided in kind, and facility managers may not have the ability to procure them directly or adjust quantities based on patient needs. If they do have direct access to funds, there may be strict regulations about the use of those funds and little flexibility in their allocation. Clinical staff might lack training in financial management, and the information infrastructure necessary for good accounting may be limited.

In addition to public funds, internally generated funds – including user fees and other revenues collected directly by facilities – may constitute a pool of discretionary funds at the facility. In some contexts, internally generated funds are controlled by facilities, while in others, facilities are required to return them to the district or central treasury. If controlled by facilities, these funds are sometimes “off-budget” (not included in the official budget) and have weaker reporting requirements.10 In many contexts, different sources of funding are intended for different portions of the facility budget, but facilities often have difficulties managing and accounting for these fragmented funds. These multiple funding flows and multiple payment methods create an incoherent set of incentives for health workers and can result in undesirable provider behaviour, such as patient cream skimming and cost-shifting.

-

To support high-quality primary health care delivery, funds need to reach frontline facilities in a timely and predictable fashion, and in full. But in many LMICs, challenges with getting public funds to lower-level facilities are common. While salaries for government employees are often paid directly from a central-level ministry, operational and capital funds often have challenges associated with disbursement.

Challenges with getting funds to frontline facilities

Common challenges to getting funds to facilities include leakage in funds transfers along the chain from central, regional, and local levels of government to facilities; and delays in disbursement.11 Public expenditure tracking surveys (PETS), which carefully triangulate what proportion of disbursed public funds are received by lower-level facilities, often reveal delays and leakages that prevent facilities from receiving operational funds. In Chad, for example, only 18% of the non-wage recurrent budget reached the regional level, and front-line providers received less than 1% of funds.10 In Ghana, a survey found that only 20% of non-salary funds reached health facilities, and in Tanzania, the estimated leakage rate – meaning funds either disappeared or were not used as budgeted – of non-salary funds was 41%.11 (For a brief overview of PETS and how to conduct one, see: Economic and Social Tools for Poverty and Social Impact Analysis: PETS.)

Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. transfer systems that require multiple steps in the payment process between the Ministry of Finance and facilities can create delays in funds reaching facilities, whether due to complex administrative procedures or leakage as funds move through the system. Such delays can translate into low budget execution rates (the proportion of budgeted funds which are spent by the end of the fiscal year) for the health sector. In Nepal, for example, approximately 20% of the overall 2012 health budget was disbursed in the final quarter of the year, resulting in District Health Officers spending only 80% of budgeted funds.12 Low budget execution rates, in turn, can jeopardize future allocations from the Ministry of Finance, which might blame the underspend on inefficient facility management rather than on late disbursements.

Delayed or irregular payments also have a negative impact on health workers and can lead to demotivation, mistrust, and absenteeism. If health workers do not receive their salaries, they may charge informal payments to patients or refer patients in public facilities to their own private clinics in an effort to make up for lost wages.11 Over the long term, staff remuneration challenges can make health workers less interested in taking a government-funded health care position in the first place, contributing to staffing shortages in the public sector.

-

Facility budgets provide an outline for how a given amount of money received from a particular source is intended to be spent. Ideally, budgets should be a tool to proactively plan for future activities and track the use of funds in real-time. Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. preparation exercises help facilities estimate how much funding they will have available and how they will use that funding. In larger PHC facilities with authority to manage their own finances, budget preparation is an essential component of planning (such as what kinds and how many medicines and supplies to buy, which staff to hire, and how to meet the evolving needs of the patients and communities the facility serves). Many smaller government-owned PHC facilities may not have this authority – staff allocations may be decided at a higher level and medicines provided in-kind – and their budgets may cover only on facility operational costs or use of internally generated funds.

Challenges with health sector budget formulation that affect funds availability at facilities

In many contexts, facility budgets are determined as part of a broader or national health sector budget formulation process. National health budgets may be set by referring to historical spending levels – what was the budget last year and did that money get spent? – and often focus on determining the funds required for service inputs like personnel, medicines, and supplies. However, historical budgets may not accurately reflect optimal spending patterns or current population health needs. Focusing on inputs or line items may distract from what outputs and outcomes should be being achieved with funds allocated.

Common challenges in health budget formulation processes at the national level that can impact funds availability at the facility level include:10

- Variability in annual amounts allocated to the health sector by Ministries of Finance or legislatures

- Weak evidence on actual costs and unrealistic revenue projections, leading to a lack of health budget credibility

- Budgets developed from historical spending patterns with little connection to annual operational plans, making it challenging to translate health sector priorities into budget allocations.

-

Appropriate tracking of PHC funds and resources for PHC is critical in effectively funding PHC.

Tracking how much is being spent on primary health care

Global health spending has grown dramatically since 1978 when the Declaration of Alma-Ata emphasized the importance of primary health care (PHC). Unfortunately, it is unknown exactly how much of that spending has gone to PHC, partly because a standard methodology for tracking PHC spending was only recently established.13 Defining spending on PHC has been difficult due to its multisectoral, multi-dimensional aspects, as well as data limitations and differences in service delivery modalities across contexts.14 WHO staff recently developed guidelines for defining and tracking PHC spending13, based on the standard S functional classifications. PHC spending includes expenditures on “first-contact” curative and preventive primary care – sometimes provided at different levels of the health system, and by a variety of different health workers depending on country's context – as well as community outreach and public health strategies that prevent illness and promote well-being.1315

How much should we allocate for PHC?

There is no global standard for the “right” percentage of total health spending to allocate to primary health care. For the 50 countries in the WHO’s Global Health Expenditure Database for which values have been estimated, the proportion of current health spending allocated to PHC ranged from 37% to 89% in 201616. Various organizations17 have estimated16 the cost of a “basic” or “essential” package of services9, although these often do not include the value of investing a more comprehensive set of cross-cutting interventions that impact health such as health literacy, sanitation, and nutrition. WHO published estimates for a set of low and middle-income countries18 of the additional resources required to strengthen health systems to provide equitable access to a comprehensive package of health services targeting the health SDGs. In an ambitious scenario, total health-care spending would increase to a population-weighted mean of US $271 per person (range $74–$984) across country contexts (2014 dollars). Stenberg et al.18 further expanded the model in 2019 to project the resources needed to strengthen PHC over the next ten years. Estimated investment needs to facilitate the delivery of a core set of preventive and outpatient PHC services PHC services refer to any intervention, procedure, regimen, or process that providers use to respond to the needs and demands of their patient population at the primary care level. Because of PHC’s community-facing orientation, services can be provided virtually or face-to-face in homes, communities, or PHC centres. Depending on the context, services may be provided by public or private providers. range from $65 per capita in low-income countries to $334 (2014 dollars) per capita in upper-middle-income countries (*recurrent costs only).

But in many low-income countries, these estimates are much higher than total health spending levels—on all levels of care combined19—which averaged just US$36 per capita in 2016 (based on analysis of WHO GHED data).7

Raising enough money for health overall, and spending enough on PHC specifically, remain challenging in many contexts.

Investing in public health

In addition to funding clinical services, spending on PHC also includes public health initiatives and other sector programs that address the underlying social determinants of health. This includes expenditure on health education (including health literacy in schools); environmental health (clean air, water, and sanitation); safe transportation systems and road safety; workplace safety; affordable housing and housing standards; food safety; children’s nutrition; and quality assurance of pharmaceuticals and medical technologies, among other programs.

-

- Budget A document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives. : a document that outlines forecasted revenue and planned expenditure for an entity (government, subnational unit, or health facility) over a defined period of time. Budgets indicate how funds are meant to be allocated to achieve certain objectives.

- Financial management Systems and processes at the facility level to track revenues and expenditures, ensure that resources are not wasted, and ensure that desired results are achieved : systems and processes at the facility level to track revenues and expenditures, ensure that resources are not wasted, and ensure that desired results are achieved.

- Public financial management The rules and regulations established to ensure transparent, effective, accountable management of public (government) finances. PFM includes all phases of the budget cycle, including the preparation of the budget, budget execution, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangements, and external audit. (PFM): the rules and regulations established to ensure transparent, effective, accountable management of public (government) finances. PFM includes all phases of the budget cycle, including the preparation of the budget, budget execution, internal control and audit, procurement, monitoring and reporting arrangements, and external audit.

- Program-based budgeting Developing budgets based on the resources needed to achieve program objectives (or produce desired outputs or results). (also known as output-based budgeting): developing budgets based on the resources needed to achieve program objectives (or produce desired outputs or results).

- Performance-based financing Providing financial incentives to providers based on the achievement of pre-defined, measurable, and agreed-upon performance targets. : providing financial incentives to providers based on the achievement of pre-defined, measurable, and agreed-upon performance targets.

- Direct facility financing The practice of directly transferring funds to health facilities for their management and use. : the practice of directly transferring funds to health facilities for their management and use.

-

Top-down budgeting

Budgeting process in which a central (national) authority determines resource allocations based on revenues available.

: Budgeting process in which a central (national) authority determines resource allocations based on revenues available. - Bottom-up budgeting Budgeting process in which health facilities or other subnational units estimate the budget needed to meet local service delivery needs. : Budgeting process in which health facilities or other subnational units estimate the budget needed to meet local service delivery needs.

- Financial protection Financial protection means that individuals and households do not experience catastrophic or impoverishing expenditure as a consequence of paying for health care. : Financial protection Financial protection means that individuals and households do not experience catastrophic or impoverishing expenditure as a consequence of paying for health care. means that individuals and households do not experience catastrophic or impoverishing expenditure as a consequence of paying for health care (World Health Organization 2010).

- Fiscal space for health Fiscal space for health is the budgetary “room” that allows a government to spend on health without undermining its fiscal sustainability. : Fiscal space for health Fiscal space for health is the budgetary “room” that allows a government to spend on health without undermining its fiscal sustainability. is the budgetary “room” that allows a government to spend on health without undermining its fiscal sustainability (Tandon and Cashin 2010).

- Revenue raising Revenue raising is the way money is raised to pay health system costs. Money is typically received from households, organizations or companies, and sometimes from contributors outside the country (called “external sources”). Resources can be collected through general or specific taxation including payroll taxes; voluntary health insurance contributions; direct out-of-pocket payments, such as user fees; and donations. : Revenue raising Revenue raising is the way money is raised to pay health system costs. Money is typically received from households, organizations or companies, and sometimes from contributors outside the country (called “external sources”). Resources can be collected through general or specific taxation including payroll taxes; voluntary health insurance contributions; direct out-of-pocket payments, such as user fees; and donations. is the way money is raised to pay health system costs. Money is typically received from households, organizations or companies, and sometimes from contributors outside the country (called “external sources”). Resources can be collected through general or specific taxation including payroll taxes; voluntary health insurance contributions; direct out-of-pocket payments, such as user fees; and donations. (World Health Organization 2010)

- System of Health Accounts 2011 The System of Health Accounts (SHA) 2011 is a methodology for tracking all health spending in a country. It generates consistent and comprehensive data on the magnitude of health spending, disaggregated by the sources of financing, financing schemes that manage health spending, the kinds of health care goods and services consumed and the health care providers who deliver these goods and services. : The System of Health Accounts (SHA) 2011 is a methodology for tracking all health spending in a country. It generates consistent and comprehensive data on the magnitude of health spending, disaggregated by the sources of financing, financing schemes that manage health spending, the kinds of healthcare goods and services consumed and the health care providers who deliver these goods and services (OECD et al. 2011).

PHCPI is a partnership dedicated to transforming the global state of primary health care, beginning with better measurement. While the content in this report represents the position of the partnership as a whole, it does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any individual partner organization.

References:

- Nakhimovsky S, Baruwa E. Securing Domestic Financing for Universal HealthCoverage: lessons in process. Bethesda,MD: Health Finance and Governance Project. Abt Associates; 2018 Jan.

- Jowett M, Kutzin J. Raising revenues for health in support of UHC:strategic issues for policy makers. World Health Organization; 2015.

- WHO. Primary health care [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2021 [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care

- Singh SR. Public health spending and population health: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Nov;47(5):634–40.

- Watson SI, Sahota H, Taylor CA, Chen Y-F, Lilford RJ. Cost-effectiveness of health care service delivery interventions in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Glob Health Res Policy. 2018 Jun 8;3:17.

- Bellagio District Public Health Workshop Participants. PUBLIC HEALTH PERFORMANCE STRENGTHENING AT DISTRICTS Rationale and Blueprint for Action. Rockefeller Foundatio; 2016.

- World Health Organization. HEALTH SYSTEMS FINANCING The path to universal coverage. World Health Organization; 2010.

- Cashin C, Sparkes S, Bloom D. Earmarking for Health From Theory to Practice. World Health Organization; 2017.

- Meheus F, McIntyre D. Fiscal space for domestic funding of health and other social services. Health Econ Policy Law. 2017 Apr;12(2):159–77.

- World Health Organization. BUILDING STRONG PUBLIC FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS TOWARDS UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE: 2018.

- Lindelow M, Kushnarova I, Kaiser K. Measuring corruption in the health sector: what we can learn from public expenditure tracking and service delivery surveys in developing countries. Pluto Press; 2006 Feb.

- Cashin C, Bloom D, Sparks S, Barroy H, Kutzin J, O’Dougherty S. Aligning public financial management and health financing: sustaining progress towardsUniversal Health Coverage . World Health Organization; 2017.

- Vande Maele N, Xu K, Soucat A, Fleisher L, Aranguren M, Wang H. Measuring primary healthcare expenditure in low-income and lower middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019 Feb 21;4(1):e001497.

- World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund. Declaration of Astana. World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund; 2018.

- Kinner K, Pellegrini C. Expenditures for public health: assessing historical and prospective trends. Am J Public Health. 2009 Oct;99(10):1780–91.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Estimation of unit costs for general health services:Updated WHO-CHOICE estimates . World Health Organization (WHO); 2011.

- Wright J. Essential Packages of Health Services in 24 Countries: Findings from a Cross-Country Analysis. the United States Agency for International Development (USAID); 2017 Jun.

- Stenberg K, Hanssen O, Edejer TT-T, Bertram M, Brindley C, Meshreky A, et al. Financing transformative health systems towards achievement of the health Sustainable Development Goals: a model for projected resource needs in 67 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2017 Jul 17;5(9):e875–87.

- Shaw RP, Wang H, Kress D, Hovig D. Donor and domestic financing of primary health care in low income countries. Health Systems & Reform. 2015 Jan 2;1(1):72–88.

- Tandon A, Cashin C. Assesing Public Expenditure on Health From a Fiscal Space Perspective. The World Bank; 2010.

- OECD. Quality dimensions, core values for OECD statistics, and procedures for planning and evaluating statistical activities. OECD; 2011.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502.

- Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010 May;29(5):766–72.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Glassman, Chalkidou. Priority-Setting in Health: Building institutions for smarter public spending . Center for Global Development; 2012.

- Terwindt F, Rajan D, Soucat A. Priority-setting for national health policies, strategies and plans. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- WHO | WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/

- World Health Organization. Towards Access 2030: WHO Essential Medicines and Health Products Strategic Framework 2016-2030. Lancet. 2017 Jan;

- Barroy H, Sparkes S, Dale E. ASSESSING FISCAL SPACE FOR HEALTH EXPANSIONI N LOW-AND-MIDDLE INCOME COUNTRIES: A REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE. World Health Organization; 2016.

- WHO. Strategizing national health in the 21st century: a handbook [Internet]. Schmets G, Rajan D, Kadandale S, editor. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250221

- Barroy H, Dale E, Sparkes S, Kutzin J, ISSUES C. BUDGET MATTERS FOR HEALTH: Key Formulation and Classification Issues. World Health Organization; 2018.

- Fritsche GB, Soeters R, Meessen B. Performance-Based Financing Toolkit. The World Bank; 2014.

- Opwora A, Kabare M, Molyneux S, Goodman C. Direct facility funding as a response to user fee reduction: implementation and perceived impact among Kenyan health centres and dispensaries. Health Policy Plan. 2010 Sep;25(5):406–18.

- Kapologwe NA, Kalolo A, Kibusi SM, Chaula Z, Nswilla A, Teuscher T, et al. Understanding the implementation of Direct Health Facility Financing and its effect on health system performance in Tanzania: a non-controlled before and after mixed method study protocol. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019 Jan 30;17(1):11.

- Soucat A, Dale E, Mathauer I, Kutzin J. Pay-for-Performance Debate: Not Seeing the Forest for the Trees. Health Syst Reform. 2017 Apr 3;3(2):74–9.

- World Bank. Results-Based Financing for Health. World Bank; 2013.

- Argentina’s Plan Nacer [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 19]. Available from: http://millionssaved.cgdev.org/case-studies/argentinas-plan-nacer

- IEG Public Sector Evaluation. Results-based health programs in Argentina and Brazil: Performance assessment report. ReportNo.:62571 . World Bank; 2011.

- Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage. JLN/GIZ Case Studies on Payment Innovation for Primary Health Care [Evidence brief available on the internet]. Washington D.C.: Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage; 2019.

- Gerler P, Giovagnoli P, Martiez S. Rewarding Provider Performance to Enable a Healthy Start to Life. The World Bank; 2014.

- Orem JN, Zikusooka CM. Health financing reform in Uganda: How equitable is the proposed National Health Insurance scheme? Int J Equity Health. 2010 Oct 13;9:23.

- Dan K, Daniel L, Godber T. Assessing public expenditure governance in Uganda’s health sector: the case of Gulu,Kamuli, and Luweero Districts; application of an innovative framework. ACODE Policy Res Ser.; 2015.

- Chee G, Picillo B. Strengths, Challenges, and Opportunities for RMNCH Financing in Uganda: Report on RMNCH Financing Assessment . USAID Maternal and Child Survival Program; 2019.

- Lukwago D. Health Spending in Uganda Implications on the National Minimum Health Care Package. ACODE Policy Briefing Paper Series; 2016.

- Government of Uganda Ministry of Health. Governmentof Uganda Ministry of Health. Health Financing Strategy 2015/16 – 2024/25 . Kampala: Uganda; 2016.

- Federal Government of Nigeria. 2017 –2030 Investment case: reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, adolescent healthand nutrition. Abuja: Nigeria. Global Financing Facility; 2017.

- World Bank. RESOURCE TRACKING IN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN NIGERIA: CASE STUDY. World Bank; 2017.

- Federal Ministry of Health, Ondo, Nasarawa, and Adamawa State Ministries of Health. National Primary Health Care Development Agency, Ondo, Nasarawa, and Adamawa StatePrimary Health Care Development Agencies. Nigeria State Investment Project(NSHIP) Performance-based financing manual . Abuja: Nigeria; 2013

- Kandpal E, Loevinsohn B, Vermeersch C, Pradhan E, Khanna M, Zeng W. Do Financial Incentives Improve the Quantity and Quality of Maternal and Child Health Services in Nigeria? . Abuja, Nigeria: The World Bank; 2019.